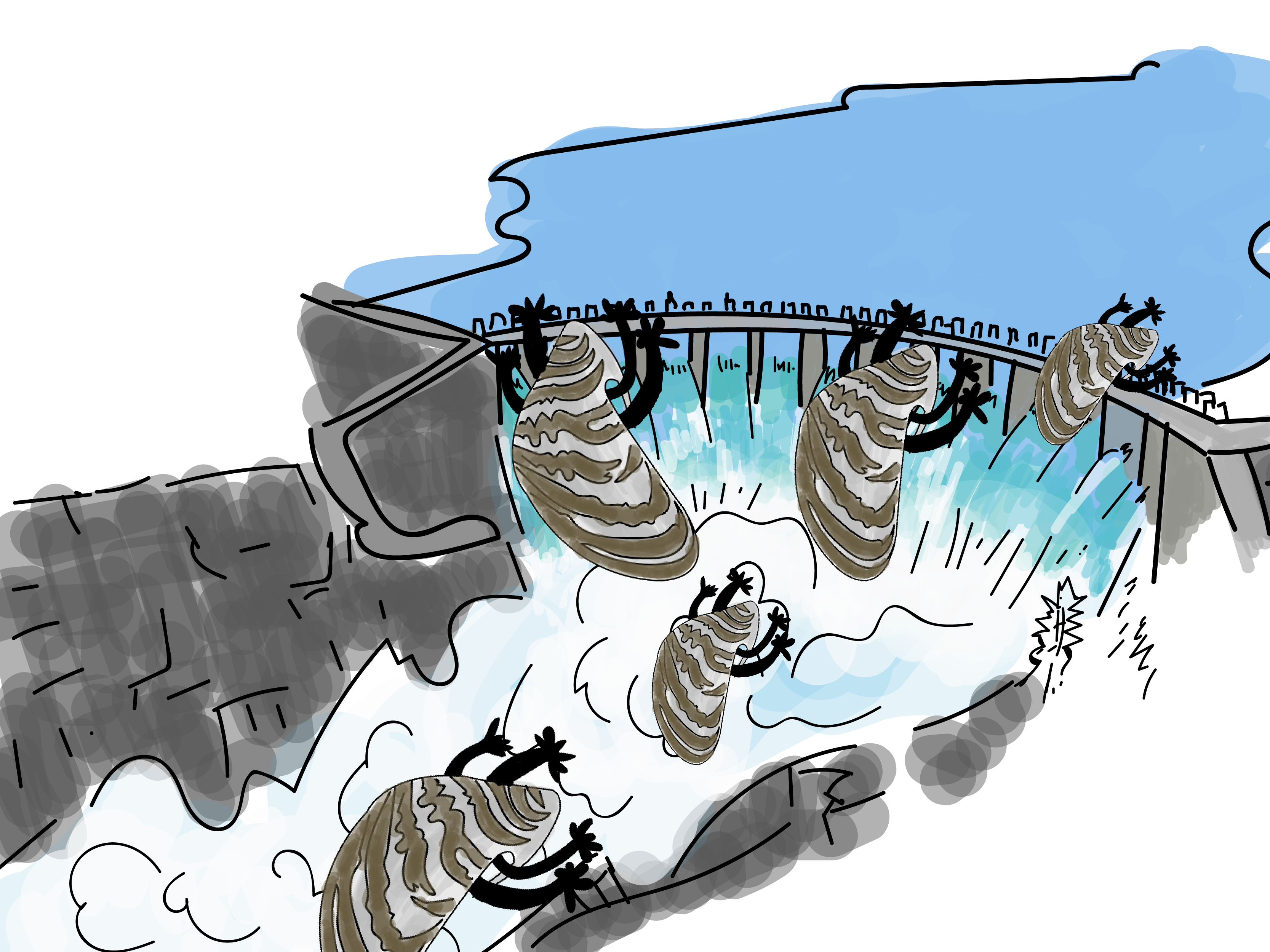

Mussels be dammed

Quagga and zebra mussels could cost tribes millions

Story by Heather Fraley | Senior Editor

Illustration by Mollie Lemm | Web Editor

THE RUMBLE of the turbines inside the inner workings of Séliš Ksanka Ql’ispé (SKQ) Dam is so loud, it’s hard to hear anyone speak. Brian Lipscomb raises his voice above the clamor to explain how the dam’s turbines are cleaned and maintained.

Acquiring the SKQ Dam, formerly Kerr Dam, in 2015 was an important step forward for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT). With the acquisition, it became the first tribal government in the U.S. to own a major hydroelectric facility. However, the CSKT still faces challenges.

The most recent threats to this facility are aquatic invasive zebra and quagga mussels. The seemingly inevitable westward march of these invaders is a source of financial concern for Energy Keepers, the tribally-owned company that operates the dam, which is located on the Flathead River. The mussels could cost the company $8 million a year, according to Brian Lipscomb, CEO of Energy Keepers and a CSKT member. Any financial loss incurred could significantly impact tribal social support programs that many members rely on.

Although no invasive mussels have been found in the Columbia River Basin, which includes the Flathead River, they have been detected as close as the Tiber Reservoir in north-central Montana. Once the mussels get into a body of water, they multiply rapidly and coat any submerged structures, such as hydroelectric turbines. Montana conservation groups and agencies spent about $9 million in prevention in 2017.

In fiscal year 2017, the dam earned $27 million in total funds for the tribal government. After operating costs are subtracted, the dam generates about $18 million a year in profit. According to Lipscomb, the dam is one of six for-profit CSKT companies. The money goes directly to the tribes.

“We have zero retained earnings,” Lipscomb said. “The tribes use those dollars to provide services to the tribal membership, and that, of course, benefits the entire community as well.”

Energy Keepers follows a specific for-profit business plan: it sells its energy on the open market. If Energy Keepers makes less energy, it makes less money. It doesn’t have customers who could share the higher operation costs mussels would bring. If the turbines are stopped, no energy is generated, and the dam loses money.

If mussels make it to the Flathead River, dam operators plan to shut down the turbines and physically remove the mussels. Lipscomb estimates $8 million a year would be lost, based on how long the turbines would be stopped.

“So that $8 million, if we suffered that as an impact, that would be a direct impact to the revenue that we provide back to the tribes,” Lipscomb said.

According to Lipscomb, some of the revenue from the dam goes toward tribal social support programs, including elderly assistance programs. The services include snowplowing to provide better winter access for elderly people and supplying firewood to heat houses. There are also programs that help tribal members who need assistance after a death in the family.

The dam generates an additional $2 million a year for the tribal natural resources department as mitigation for the loss of wildlife habitat caused by the dam.

If invasive mussels get into to the Flathead River, the mitigation funds won’t stop coming in. Mitigation payments are required in the dam’s operating license. However, invasive species impact these funds in a different way.

According to Tom McDonald, manager of the CSKT Division of Fish, Wildlife, Recreation and Conservation, the funds are flexible and protect the native fishery in multiple ways.

The natural resources department has already redirected some of its mitigation funds from other planned projects to invasive mussel prevention.

This reduces the funding to provide fishing opportunities for some tribal members who rely on fish for food. It also reduces the ability to improve the fishery for the native bull trout, a threatened species of high cultural significance to members of the CSKT.