Dealing with drift

Montana’s organic farmers face limited options for compensation

Story by Jenny Gessaman | Staff Writer Photos by Gabby Friedlander | Staff Photographer

ON A BREEZY May day in 2008, Daryl and Linda Lassila were doing what they do most spring days: yard work. The Lassilas are farmers, so once the snow has disappeared and the soil begins to warm, they are almost always outside getting their land prepped for planting.

Daryl can’t remember exactly what they were doing that day—it was 10 years ago, after all—but as he tries to conjure the details, he suspects they were probably mowing the lawn, or perhaps building their garage. A decade later, the white exterior is covered in gray metal, and the garage door still rides up and down.

There is one thing Daryl is certain of: a small, single-seat airplane flew overhead, its overpowered engine howling across the sky. “It was on what I would call a nice, breezy day. They call it a calm day, the applicators,” he said. There was a wind, one too weak for dust devils but strong enough to bend the grass.

Daryl Lassila, a fourth-generation farmer on his family’s property in Great Falls, Montana, began transitioning to organic farming in 1998.

“Applicators” is short for aerial applicators, pilots who use specially equipped planes to spray insecticides and herbicides, on large swaths of farmland. And the plane that flew by was unmistakable. “That guy has really sharp paint jobs,” Daryl said. “It’s not just a generic airplane.”

The Lassilas gazed skyward, following the plane as it beelined toward a neighbor’s field. Why was a crop duster arcing over their acres? They didn’t hire spray pilots. They couldn’t: Their home is surrounded by organic farmland, and organic certification bans most pesticides. So what was going on?

Daryl jumped onto his ATV and roared after the speeding plane. His fears confirmed, he pulled over to avoid the plane’s blanket of toxic broadleaf herbicide. He snapped a few pictures with his phone and raced home to grab his truck.

He caught up with the plane as it landed, and the pilot climbed out to a man demanding answers. “The pilot blamed it on his planes going so fast, they went over our field,” Daryl said dryly.

The pilot followed his excuse with a proposal to pay for his misdeed. The gesture was remarkable for two reasons: it was an admission of guilt, and chemical contamination of organic cropland can cost thousands of dollars. The offer was conditional, however. Daryl couldn’t report the pilot, or how the herbicide had drifted straight into an organic field of Austrian winter pea.

•••

Montana’s farmers have a gambling problem. Their profession is a yearlong game of chance that pits man against weather, a game where late rain, high temperatures and heavy hail are all losing hands. Low-volume, high-priced organic crops raise the stakes even higher, stakes farmers are almost guaranteed to lose in the game of drift.

The drift of chemicals from non organic neighbors decreases profits, reduces the amount of arable land and can even damage social standing for organic farmers trying to provide consumers with chemical-free crops and foodstuffs. It also triggers an onerous process to retain organic certification and receive compensation for what amounts to pollution of their commercial crops.

For four generations, the Lassilas have farmed wheat and barley around a winding coulée 10 miles northwest of Great Falls. The shift from chemical farming was gradual and started when Daryl returned home. His graduation from Great Falls High School had kicked off years of “seeing the country,” an experience Daryl said confirmed his desire to return to the farm and continue the family tradition.

He was still working under his dad, Robert, when he suggested organic. Robert gave him two acres of farmland to experiment with, but Daryl had bigger plans. “Being as I was at that time managing the farm, I took 100 acres and flew with it,” Daryl laughed. Organic worked, and Daryl transitioned 100 acres each year until the farm was fully organic in 2013.

Organic is more than a name, it’s a label representing a rigorous and regulated set of farming practices. Authorized by Congress in 1990, the National Organic Program (NOP) spent 12 years building its organic requirements and was only considered fully operational in 2002. NOP standards ban most synthetic substances, including the majority of pesticides, and provide protocols for when organic crops are exposed.

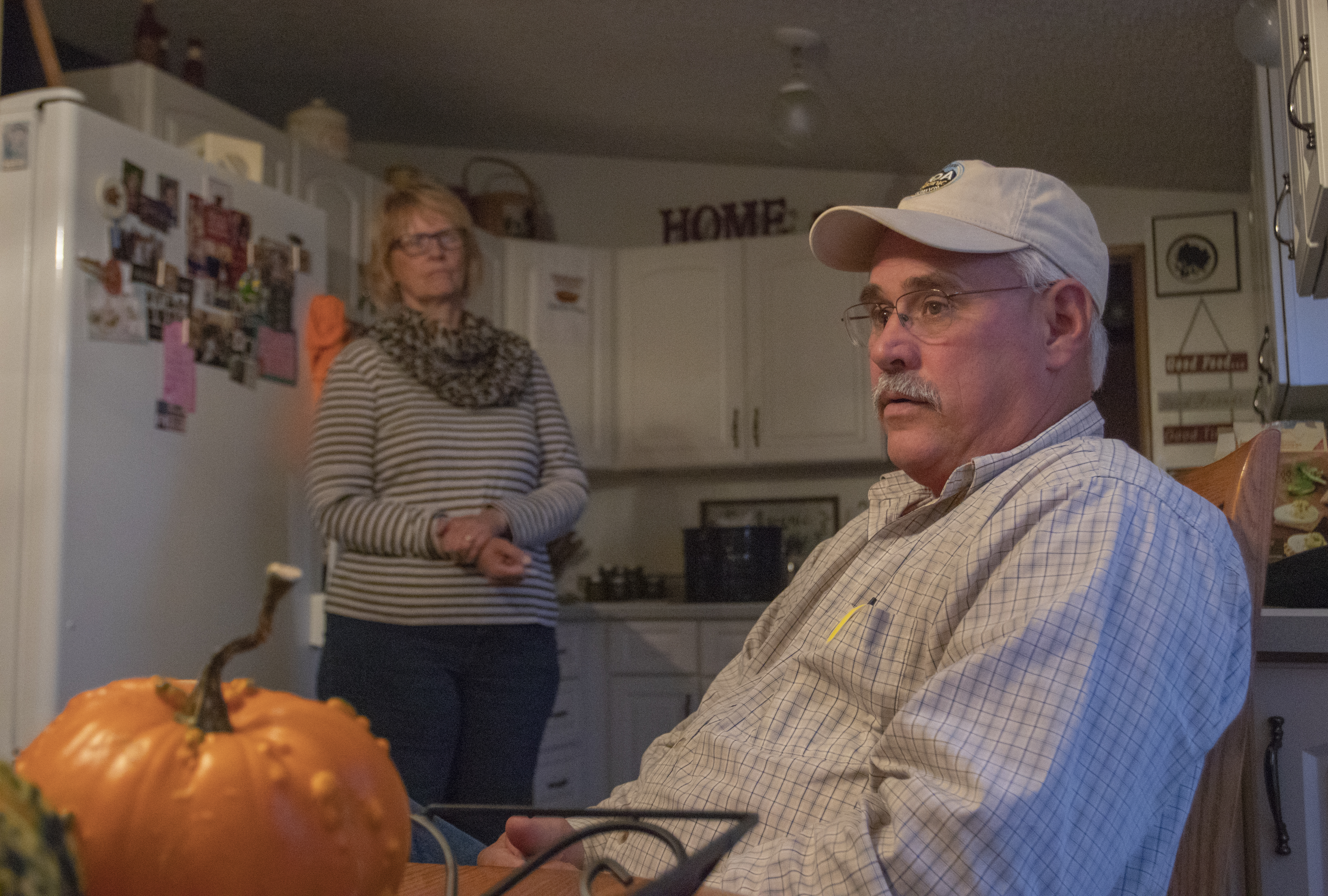

Daryl Lassila, a fourth-generation farmer outside Great Falls, Montana, was shunned by the community when he threatened to sue his neighbor for compensation after his organic farm was contaminated by a herbicide. His wife, Linda, and family stood by his side.

The first step is for farmers to “immediately notify the certifying agent.” Anyone interested in defining that phrase has to dig further into the rules. The national program is administered at the state level, leaving farmers with three sets of laws to dig through: federal law, state law and state administrative law. The last refers to the laws defining state agencies.

A “certifying agent” isn’t actually a person, but an organization. A list of 80 national and international agents, including the Montana Department of Agriculture, is available from the USDA. The logistics of notification aren’t as clear. Federal law requires organic farmers to report drift, but doesn’t say how. The Montana Organic Policy Manual reads the same. The state’s pesticide division website offers some guidance. It says anyone “suffering…from the improper use of pesticides” should report by telephone, email or mail.

•••

Pesticide drift is a national problem. Although comprehensive statistics are hard to come by, Kevin Bradley, University of Missouri professor and plant pathologist, estimated 3.6 million acres of soybean were damaged by Dicamba drift in the first 10 months of 2017. He only reached this number by repeatedly requesting information from 25 states’ departments of agriculture.

Drifting Dicamba, a hard-to-control herbicide, has made national headlines for the last several years. Weeds have developed resistance to common

herbicides, and Monsanto has created genetically modified crops that can tolerate Dicamba, a benzoic acid herbicide that controls annual and perennial broadleaf weeds in grain crops and grasslands. It is particularly volatile, and doesn’t stay where it’s put.

In the Southeast, Dicamba drift is damaging soybean and cotton crops. By August 2016, Missouri farmers had reported more than 42,000 acres of crop damage, according to an EPA advisory. The Wall Street Journal reported Missouri and Arkansas combined were estimating 200,000 acres had been contaminated.

Drift has even escalated to violence. In December 2017, Missouri farmer Allan Curtis Jones was found guilty of shooting neighboring farmer Mike Wallace over a Dicamba drift. A year earlier, the two had met along the Arkansas-Missouri border to work out a dispute. Wallace had filed a report claiming Dicamba drift was coming from the farm where Jones worked. The conversation became heated and 28-year-old Jones shot 55-year-old Wallace, after Wallace allegedly grabbed his arm.

The problem is fatal for more than crops and farmers. Herbicides like Dicamba are designed to kill unwanted vegetation, meaning they can affect wide ranges of plants. Last September, National Public Radio highlighted the Dicamba damage to centuries-old cypress trees in Reelfoot Lake, Tennessee.

Daryl’s parents grew “all chemical” wheat (left) and barley on their land. Since 2013, Daryl has successfully grown certifiable organic wheat (right) and many more crops free of chemicals. Going organic requires adherence to stricter governmental standards. Organic products must undergo a series of government tests and investigations to maintain their labels.

The chemical also kills milkweed, the only plant monarch butterflies will lay their eggs on. Roughly 70 million acres of the insects’ migratory habitat in the South and Midwest will be hit by Dicamba drift by 2019, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

•••

Montana’s Pesticide Compliance Program is the Department of Agriculture division responsible for keeping pesticide use in line with the law. Pesticide Compliance Program Manager Leonard Berry explained that all applicators are required to follow federal “label law,” meaning products must be applied according to directions listed on their labels. Because most labels say “do not drift,” drifting those products is unlawful.

Drifting your neighbor may result in fines ranging in the hundreds of dollars, similar to traffic tickets. In egregious cases, malicious pilots can have their spraying licenses revoked, but Berry said it has never happened.

Despite the rules, Berry added, drifting is inevitable. “Every single pesticide application drifts, whether it’s an eighth of an inch, an eighth of a mile or eight miles,” he said. This means Berry’s department needs one more piece to open a “drift incident” case: the affected neighbor. “If your neighbor says it’s not drift, it’s not drift,” he said.

Daryl said it definitely was drift. He turned down the pilot’s offer and reported the infraction, setting Berry’s staff in motion. Their investigations are based on vegetation and soil samples sent to the Department of Agriculture’s Bozeman laboratory to confirm whether drift occurred. The process also includes interviewing all farmers involved, and determining wind direction and speed on the day in question.

Quinn weighs some of his produce from the fall harvest, mostly melons and carnival squash. He compares the weights of this year to those of the previous year. These vegetables are for family and friends.

In Daryl’s case, the results were clear. The pilot hired by the Lassilas’ neighbor had drifted. The pesticide program made its determination and ended its investigation. But how much damage had been done, and wasn’t Daryl owed compensation? For those questions, he had to turn elsewhere in the Department of Agriculture, to the Montana Organic Program (MOP).

MOP’s investigations focus on organic integrity and specify what a farmer must do to maintain organic certification. In the Lassila case, Daryl was told 40 acres had been affected. He could not grow organic on those acres for three years and had to submit new organic farming plans reflecting that change.

Neither the pesticide program nor the organic program were obligated to assist or compensate Daryl for economic losses resulting from the applicator’s actions. That was up to him. He could walk away, he could negotiate with the applicator and the neighbors, or he could sue.

•••

Until April 2018, Bob Quinn managed a family farm that started in 1920. He spent four decades building an organic operation focused on small grains, one best known for the ancient wheat Quinn trademarked, KAMUT.

In the late 1990s, the Quinn Farm and Ranch was drifted. The air was still, the weather was quiet and the pesticide was volatile. The pilot hired by Quinn’s neighbor dropped a load of Dicamba on a target a half-mile away. Accuracy didn’t matter, though. “The herbicide acted as a cloud and drifted over half a mile,” Quinn said. “It was at a time when the lentils were blooming, so it sterilized the crop and I didn’t get a single pod.”

Carnival squash line the floor of Bob Quinn’s garage.

Quinn reported the 80-acre drift, and the state tested the crop. The results revealed trace amounts of herbicide, but amounts well below the organic limit. The field kept its organic certification, which proved useless when the sterilized plants never produced a crop for Quinn to sell.

He estimates the drift cost him roughly $16,000. “That was probably 30 percent of my expected profit for that year,” Quinn said.

There was, however, one way to get the money back. Trace amounts of herbicide meant Quinn could sue his neighbor. But he couldn’t. Quinn’s reasoning was cautious and deliberate. The loss was big for Quinn Farm and Ranch. There was also the principle of the thing. No one was at fault, and there was no malicious intent. “I wouldn’t dream of suing my neighbor,” he said. “We work together, we live together, we exchange food and help each other from time to time.”

Organic Dakota Sport tomatoes are part of Bob Quinn’s dry land experimental plot and personal garden in Big Sandy, Montana.

The idea that someone like Quinn, wronged through no fault of his own, is left to absorb financial losses caused by someone else’s actions is not an idea Neva Hassanein likes.

“I don’t think the state’s taking this sufficiently seriously,” the University of Montana professor of environmental studies said. “These are people’s livelihoods at stake.”

Hassanein’s research on contemporary food systems has familiarized her with the aftermath of pesticide drift. The laws, she said, are designed to guide state officials and offer little assurance for organic farmers. Growers are left on their own when it comes to restitution and she worries the whole process is just “passing the buck.”

“[The farmers] are often forced into courts for the loss of their crops, or even the potential threats to their health,” she said. “It puts this tremendous onus on the victim basically.”

The fact upsets Hassanein, especially considering the high stakes of organic farming. A crop exposed to pesticides cannot be labeled organic, meaning any sale would earn a lower, nonorganic price. This may not cover the increased cost associated with raising organic products, leaving farmers in the red.

Some organic farmers choose not to sell a drifted crop at all. Hassanein knows several Montana farmers who adopted organic not just as a business practice, but also as a philosophy. Morally, she said, they cannot justify selling a pesticide-exposed crop to their customers.

That leaves one uncomfortable option. “Your only recourse is to try and sue your neighbor,” Hassanein said. “And that does not make for good neighborly relations.”

•••

Daryl was now a solitary but determined player in a high-stakes game. With records splayed out and a copy of NOP law at hand, Daryl calculated the cost of the pilot’s mistake. “That was a pain in your butt there, alright,” he said. “I figured it out, and I was very lenient for him.”

Lenient because Daryl did not charge for the hours he spent calculating. Crop loss is more than lost sales. It includes lost “crop inputs,” including the expenses involved in growing a crop, time spent farming and purchasing seed.

In the late 1990s, Bob Quinn’s farm faced numerous cases of pesticide drift.

Organic farmers also have to consider the costs of adhering to federal NOP laws. Laws like Section 7 CFR § 205.202 (b), which bans the application of prohibited substances on farmland for three years prior to growing organic crops. This meant the organic Lassila farm, drifted with a broadleaf herbicide prohibited by NOP, lost use of its drift-hit land for three years.

Daryl tallied the missing profits year by year, coming to a total between $10,000 and $20,000. “It was a reasonable amount, in his pocketbook, at least,” Daryl said. “It cost me a little bit more.”

Daryl just wanted to break even. He repeatedly presented the total bill to the pilot over the next six months, to no avail, and was eventually forced to pull another player into the game: the neighbors who had hired the pilot to spray their land. Daryl grabbed his numbers and went next door. “They were kind of in shock,” Daryl said. The pilot had assured Daryl’s neighbors that everything had been settled. “They were pretty quiet when we passed [them] the bill,” he said.

When the neighbors also refused to pay, the Lassilas played the only card they had left. Robert, Daryl’s 70-year-old father, drafted a lawsuit naming the pilot and the neighbors. The matter never went to court, and when payment came 12 to 16 months after the drift, it came with a steep price.

“I was all but threatened,” Daryl said. “I was shunned by all the neighbors.”

It came in small gestures, actions amplified by the empty space of rural Montana. No one waved as the Lassilas passed. Trucks never stopped on the two-track gravel roads, never rolled down windows for a conversation about the harvest and the weather. “There wasn’t an empty chair when you went to farm meetings,” Daryl said.

But the Lassilas had been growing grain for four generations, putting roots in the community as they put roots in the ground. They hoped every local farmer remembered their career is a gamble, that every neighbor understood the Lassilas were trying to make ends meet.

No one did, and the family isn’t bitter about it. You see it in any neighborhood, they say, and the ice began to melt after a year. Things went back to normal, more or less.

Now, the Lassilas add, the farm is proactive, hedging its bets for the next round. Daryl makes sure neighbors and local applicators know Lassila crops are organic. A sign just off the main road declares, “ORGANIC FARMING NO SPRAY ZONE.”

Nevertheless, the Lassilas are resigned to a next round. That’s something both Daryl and Berry agree on. Drift is inevitable. The only question is, who should pay for it?

Safflower seeds are grown on Bob Quinn’s farm. He presses seeds into oil in his barn.