Public Health Exodus

Local healers leave after divisive legislative session

Story by Addie Slanger

Photos by Joseph Evans

Illustration by MaKayla O’Neil

Matt Kelley was finishing dressing the turkey on Thanksgiving, 2020, when his wife called him into the other room. Peering out the window, he saw a small group of men on the sidewalk outside his home holding signs, a Weber grill and a live, white turkey on a leash.

The signs labeled Kelley a “tyrant,” and called for him to resign as lead health officer of the Gallatin City-County Health Department in Bozeman, Montana. The protestors weren’t happy Kelley had enacted a county-wide recommendation for families to have smaller holiday gatherings. Kelley found out the grill was for burning face masks. He still isn’t sure what the leashed turkey signified.

Perhaps some holiday spirit.

At the time, the COVID-19 pandemic was worsening in Bozeman. Dozens of people filled the hospitals and health officials were hoping Montana was experiencing the worst wave of the pandemic it would ever have to face.

The small Thanksgiving protest marked the first of consecutive weeks of picketing in front of Kelley’s house from the same group of people. It was a hard time for him and his family.

“My kids were both under the age of 12,” Kelley said. “It’s hard for them to understand why there’s someone on the front sidewalk calling daddy a tyrant and demanding his resignation.”

Seven months later, Kelley left his role as top health officer in Gallatin County to join the Montana Public Health Institute as its first chief executive officer. He’s not the only Montana public health official to have left his position since the pandemic arrived on the shores of the United States.

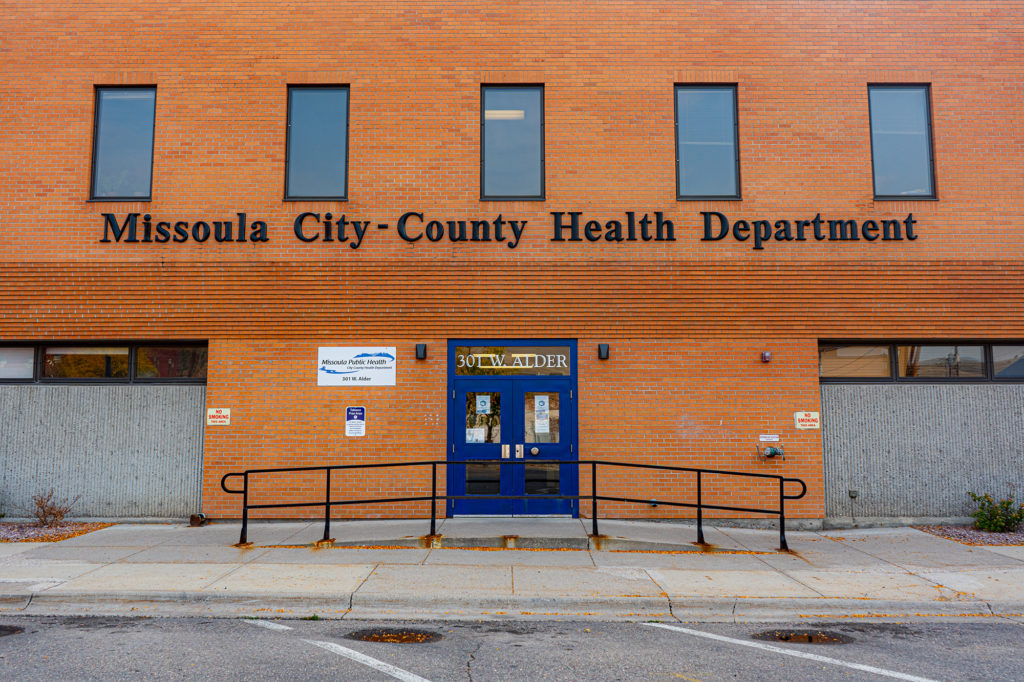

In the last year, more than a dozen Montana counties have lost their top health official, according to data from the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS). This includes four of the state’s seven most populous counties: Missoula, Gallatin, Flathead and Butte-Silverbow. And this exodus hurts public health efforts in Montana, where important health action occurs at the local level, said Ellen Leahy, former director of the Missoula City-County Health Department for more than 30 years. The loss of established top health officials means the loss of important institutional knowledge.

At least 17 of Montana’s 56 counties — more than 30% — have seen the transition of their top health official; a trend occurring across the United States, labeled by ABC News as the largest exodus of public health officials the nation has ever experienced.

In Montana, much of the health officers’ frustration comes from the legislation passed in the 67th Montana Legislature, on the heels of a red wave in the 2020 election, said Jim Murphy, former bureau chief of the Communicable Disease Bureau for DPHHS. Legislators worked to strip the authority from local public health departments in the form of legislation like House Bills 257, 121 and 702. HB 257, now law, prohibits local health boards and officers from creating policies that “restrict the ability of a private business to conduct business.” HB 121 allows a government body to amend local health regulations and revises penalties allowed for the violation of a local health rule.

But of most concern to Leahy, Murphy and health officials around the state is House Bill 702, legislation that significantly impedes health officers’ abilities to regulate, mandate and keep track of vaccinations. The bill, which passed in April, during the final hours of the 2021 Legislative Session, prohibits public and private employers from “discriminating” based on vaccine status. It is the only legislation of its kind in the U.S., according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

In a state where public health success is dependent on local authority, Leahy said, state legislation is working to limit the power of public health officials. Montana can’t afford more public health staff cuts or transitions, Murphy said.

“You lose a lot of institutional knowledge,” he said. “You know, when [top health officials leave], it’s a bad time to lose institutional knowledge during an event [like the pandemic].”

“There’s been political differences my entire career, but they have never been as divisive as they are now. We have pushed at the state level at every session. And this year we couldn’t stop it,” Leahy said of HB 702. “Again, you see that magnification of that divide. And that symbolism shows contempt for any type of public health.”

Eventually, Murphy said, top public health officers just got tired of the political war.

“I think between the Legislature, between the perception … that public health is the enemy and not the virus, has led a lot of people to re-evaluate their options,” Murphy said. “You don’t need people threatening your family. You don’t need people protesting outside your house like Gallatin County had.”

Top health officials left their positions in Blaine, Butte-Silverbow, Carbon, Carter, Dawson, Flathead, Gallatin, Granite, Meagher, Madison, Missoula, Park, Pondera, Powell, Powder River, Ravalli and Sanders counties. An in-depth analysis of this trend points to a delegitimization of public health, and the steady stripping of its power.

The Pandemic and the Legislature

Over the last year and a half, the COVID-19 pandemic has wracked Montana. The state has seen more than 2,000 deaths and more than 150,000 cases total. September and early October 2021 saw case peaks matching Montana’s highest-ever numbers from last winter.

In addition, the state has experienced a tidal shift in politics. In November 2020, Greg Gianforte was elected the first Republican governor of Montana in 16 years, and not a single statewide Democratic candidate won election.

The following legislative session saw a tsunami of conservative legislation passed that had previously been blocked by Democratic governors for years. Gun deregulation, anti-abortion measures and anti-transgender laws surged through the House and Senate for an expected Gianforte signature. Now, many of these new laws sit suspended in court as opposition groups challenge their constitutionality.

Rep. David Bedey, a state legislator from Hamilton, sponsored HB 121, the legislation that requires local government officials to approve any public health regulations. He worked closely with public health officers to draft the bill.

The impetus for his legislation, Bedey said, was to ensure rules are actually implemented by those who are publicly elected. That is, since public health officers are appointed to their positions and not democratically elected, they should not be in charge of enforcing public regulations.

Bedey agreed he saw a connection between Montana’s public health trend and the 67th Legislature’s impact. But he said he thought public health officials would be facing the same delegitimization regardless of any bills put forth by the Legislature.

“I suspect that there is some truth to the fact that there’s a legislative tie [to public health officials’ exodus],” Bedey said. “But I think that public health officials would be facing the same sort of dilemma right now, even in the absence of any legislation during the last session.”

For example, Bedey said, he had been working on his bill before the pandemic began. COVID-19 just provided a more dramatic environment. Now, with the hyper-partisan nature of the nation, he said he thought the state could be poised for something like this to happen.

In fact, he said, he wrote HB 121 in an effort to fight the concerning trends he’d been seeing.

“My primary motivation for writing 121 was not to neuter public health, but rather, provide them the legitimacy so that they could do the work they must do,” he said. “And the way I thought that legitimacy would be established, would be that any regulations that are promulgated in a county or jurisdictional setting would be approved by people that were elected.”

Still, perhaps no legislation was more difficult to reconcile, especially for public health officials, than HB 702, Leahy said. She and the heads of other Montana public health offices had successfully fought legislation that rolled back immunization requirements, like HB 702, for over 15 years. But this year, amid widespread vaccine skepticism and public health under increased scrutiny, the bill passed.

On Wednesday, Sept. 22, a lawsuit, filed on behalf of the Montana Medical Association and various other clinics and patients, challenged the legality of HB 702. And on Oct. 6, a law firm in Sidney, Montana filed a second lawsuit against the bill.

Checked or Checkmated: Health

Officers’ Frustration

Nick Lawyer became the top health official of Sanders County in January 2021. He focused on his clinical work and enrolled in a class at the University of Montana to further improve his abilities as a public health leader.

But soon, Lawyer noticed legislation creeping through the Legislature that considerably impacted his ability to perform his job.

“In March, April, there were some bills that came through the Legislature that were very much presented as, ‘We are going to give control back to the community away from the tyrant officers across the state,’” Lawyer said. “And those bills had a pretty negative impact on our ability to do the job. And so you know, by April, by May, I found very quickly I had minimal ability to enact anything.”

That wasn’t a problem at first, Lawyer said. School was wrapping up, the vaccine had been made available to everyone, summer was on the horizon. In many ways, it felt like the light at the end of the tunnel.

Then things started changing.

Lawyer watched his position turn into a purely advisory role after the legislative session as the pandemic began to gain more steam. He wrote letters to the schools in his county and attended fair board meetings urging mitigation measures. He spread as many educational resources as he could. But he was met with mixed responses, hesitancy and disregard.

“Telling the schools, ‘you should consider masking because we know masking will reduce the spread of disease and will keep kids in school’ — simply telling the schools that caused consternation and irritation,” Lawyer said.

“So again, it’s very frustrating to be asked to fill this job, to be told this is an advisory role by the Legislature. And then when you give advice, it’s met with hostility from the community,” he continued.

In a meeting in July, four women began questioning the Sanders County public health nurse about vaccine efficacy and credibility. Lawyer marked this as an important shift in his time as public health officer. After the July meeting, people started coming more frequently, asking the board to call for Lawyer’s resignation.

Then, a woman he had never met died from COVID-19 in his county. The woman’s family blamed Lawyer for her death, claiming his policies prohibited her from receiving unproven treatments like ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.

“They asked the commissioners for a special meeting,” Lawyer said. “And the commissioners called that meeting and her widower stepped forward and said ‘Nick Lawyer killed my wife, because his policies and protocols wouldn’t let the doctors give my wife ivermectin.’”

From that moment, he was ready to be done, he said. His position had become political, not medical. He felt his hands were tied to begin with and the time he spent at the health department took away from the time he could spend at his own clinic.

When the county commissioners requested he resign, he did so.

“The job has become a political post,” Lawyer said. “It’s become an advisory political post, and you can’t really do anything, or enact public health measures. From a medical perspective, you are politicians.”

Lawyer’s experience is a microcosmic example of what many public health officials across Montana have faced. Lawyer, Kelley and other officers who have resigned or transitioned out of their positions, including the entire health department of Pondera County, were tasked with protecting their communities’ welfare while handcuffed by the legislation enacted in March, said Murphy, the retired DPHHS officer. It is a daunting assignment.

Each experienced nuanced challenges — and it’s impossible to point to one specific catalyst that prompted the exodus.

“I think some of [the health officers] just, you know, came to the point where they felt like, whatever they would do, or whatever they could do, was going to be either checked or checkmated. And it was futile to try to keep doing the same thing,” Murphy said.

The vilification of the health officers didn’t help either, Murphy said. In the legislative session, public health officials were compared to brown shirts and Nazis. Lawmakers perpetuated myths about microchips in the vaccine, he said.

The rhetoric was as bad as the actual legislation, Murphy said, and at a certain point, that became tough to navigate.

Public Health’s Prognosis

So what does this mean for the future of Montana public health? Each public health officer agreed the loss of institutional knowledge will be damaging for the state. Many of the public health practices are complicated, and require time to learn and improve.

And even more than that, legislation is much harder to reverse than public opinion. Murphy said the laws undermine the entire effort of local health officials. Once the bills become law, they’re hard to overturn.

Not only that, the anti-public health rhetoric has worked to slowly strip away the credibility of local health departments and officers. Once that happens, it’s hard to get that credibility back.

It’s the kind of thing an election and a new wave of politicians may not be able to fix, Murphy said.

“It takes a long time for that pendulum to swing back when you’ve codified some of this in statute,” he said. “So, even if the legislative body changes, or the governor’s party changes again, I’m not sure that’ll be enough.”

“We definitely lost past expertise. Definitely,” Leahy said.

“The consequences [of this politicization of public health] to medicine and to public health is a deep legitimization and a vilification of experts,” Lawyer added. “Not just in medicine, but in lots of things.”

However, many like Kelley are able to see past the difficulties to a Montana still full of health officials who care and work hard, despite the roadblocks, name-calling and dangerous rhetoric.

“What happened to me last November was really hard,” Kelley said. “But, you know, I had a lot of support. I can tell you I speak to elite health officials all over Montana … we’ll continue to work around [the challenges]. We’ll find ways to keep working for the benefit of our community.”

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Copyright © [hfe_current_year] Byline Magazine